Manufacturing and the US Economy

The US manufacturing sector is ~10% of GDP (~$3 trillion), and the US is the second-largest manufacturing country. Yet many see the US as a manufacturing failure and prefer extremely blunt government-directed policies.

I think the underlying causes of this malaise are both misunderstood and misdiagnosed. The US excels at high-volume manufacturing, but not low-volume manufacturing. The US can revive low-volume manufacturing with markets and technology once we understand the issue. The following are the main points:

-

The US does a lot of manufacturing, but it's tilted towards high-volume, static, and boring products.

-

The US performs poorly in producing short lead time, custom parts.

-

Long lead times and soft costs, fueled by the world-leading US wages for "white collar" work, are the root cause of poor performance in low-volume production because there are few units to spread the soft costs over.

-

The same world-leading wages create massive demand for short lead time parts.

-

New end-to-end digitized manufacturers, some already reaching unicorn territory, eliminate almost all soft costs and drastically shorten lead times with instant quoting and production-integrated software.

-

The number of intermediate manufacturing companies will consolidate drastically because the digitized value structure is superior, leading to much larger firm size, and making these companies great investments.

-

AI is an accelerant for these startups.

-

Flexible and affordable low-volume production makes military procurement and production of capital goods more efficient.

-

Almost all active policies make things worse by misallocating talent. The focus should be on reducing calendar time for various government approvals and certifications.

-

Flexible manufacturing keeps the US on the technology frontier and resilient to supply shocks, making China less of a concern.

-

The sum is that physical technology cycles can go much faster once these new business models permeate the economy.

Understanding the Manufacturing Industry Today

Why Do Manufacturers Exist?

The rhetoric about manufacturing can lose sight of the core organizing principles. Why doesn't one country produce all the manufactured goods? Why are there multiple factories or only one factory for certain goods? Why doesn't every home produce its own steel?

There are three main forces at work:

-

Specialization

Manufacturing is complex and competitive. It pays to specialize. The cornucopia of human desires and variation in conditions is so great that no single region can dominate everything. There aren't enough people and resources to collect the near infinite amount of knowledge needed.

-

Economies/Diseconomies of Scale

Most manufacturing reaches diseconomies of scale before global saturation. Then the rational thing to do is distribute the facilities to minimize transportation and other costs. Cars, gasoline, lumber, and cement are examples of products usually produced and consumed regionally. Other products, like concrete, sand, or certain types of light manufacturing, have local markets.

There are a few product categories with slowly diminishing returns to scale and very low shipping and localization costs, pushing them towards global production. Flat screen TVs, computer chips, ships, and phones are this way.

-

The Gravity Model

Most economic transactions occur between parties near each other. Transaction density decreases rapidly with distance. These models can be so accurate that they've discovered lost ancient cities.

The reasoning for gravity models is friction from transportation costs, transit time, cultural/language differences, and human relationships. It is easier and cheaper to get deals done close to home. But a few items are so scarce that it is worth the distance.

Even if one country is superior at production at the factory level, other costs mean it usually cannot dominate the market.

The net result is that most products are produced near buyers, even if there are other costs and productivity differentials. Richer countries substitute more capital for labor because of higher labor costs.

US Manufacturing's Hollowness

A few attributes stand out for the most economical products to produce in the US. These match what we'd expect from the gravity model, specialization, and economies of scale.

-

High Transportation Costs

Items like sand or cement, where transportation is a high portion of cost, tend to be domestically produced. Same for bulkier items like cars, dishwashers, etc.

-

Needs Speed to Market

Perishable items or other time-sensitive applications can get boosted.

-

High Volume for Fixed Cost Absorption

Any manufacturing process or run requires some setup or tooling. The work can include programming robots, organizing processes, designing molds or dies, among other activities.

The simplest way to reduce the setup burden is to produce high quantities of the item, spreading setup costs over many units.

-

Long Product Lifecycles

Static designs can often remain in the US because retooling and new equipment are rare. Or the firm can safely invest in automation, knowing it will have ample time/quantity to pay off.

-

Technological Complexity

Some technologies are challenging to manufacture, and US firms are among the world leaders. Drilling rigs, PDC bits, frac fleets, gas turbines, combines, sprayers, stealth fighters, and commercial aircraft are a few examples. Development cycles are long and R+D is significant.

-

Amenable to Mechanization and/or Automation

Some processes are easier to automate or mechanize than others. Chemical processing is an example of a process that is easier to automate, and the US is strong in (low feedstock costs also help).

Almost all the forces push US manufacturing towards high-volume, static, bulky stuff.

Low-volume products are not profitable for the majority of US manufacturers. More dynamic US manufacturing requires economical production at lower volumes.

The Structure of the US Manufacturing Industry

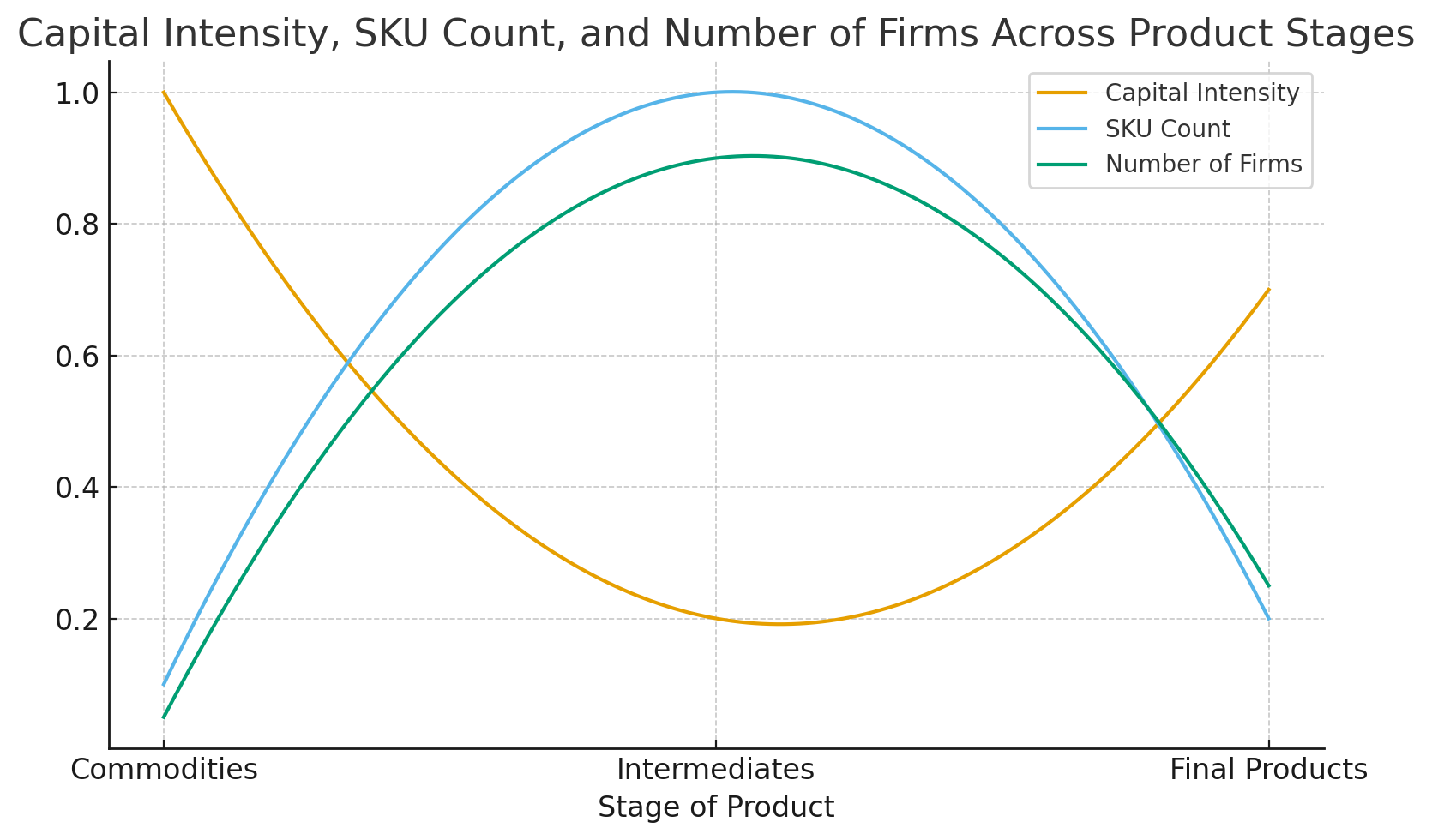

Layers of firms handle physical production. There is a spectrum from raw materials to final goods.

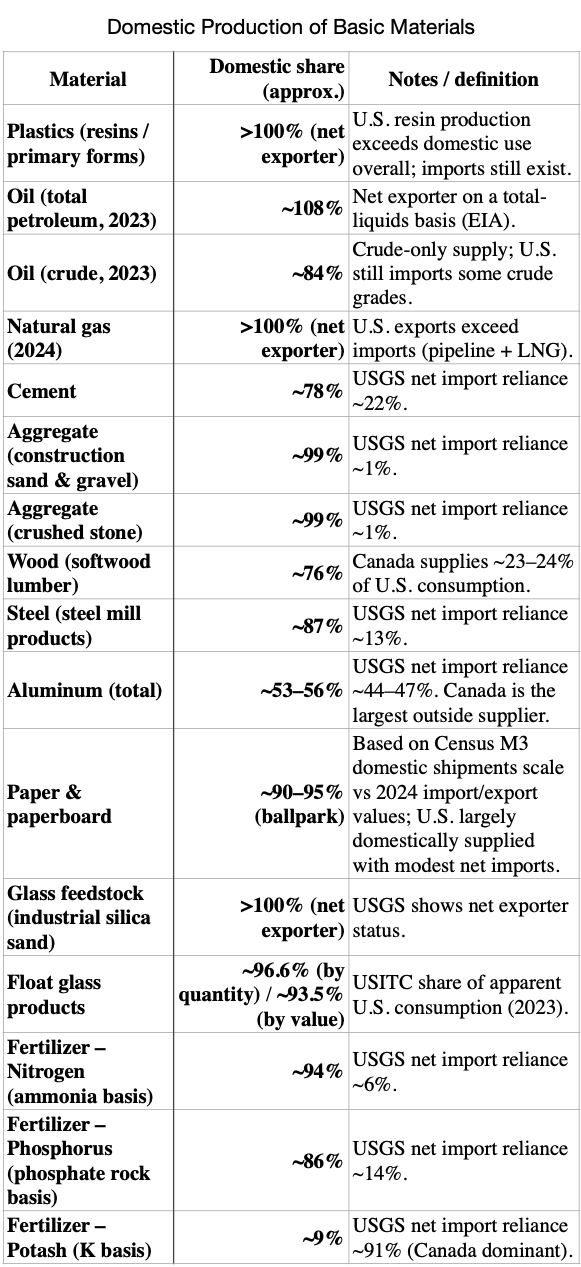

There are relatively few raw materials, like steel or plastic. The scale is massive since they serve many markets. The scale, sales volume, and commodity nature drive production to happen in gargantuan, capital-intensive facilities. The table below shows the US is almost self-sufficient in high volume basic items and the exceptions are where Canada has especially good resources.

High volume, cheap materials favor domestic production. Source: GPT-5

Firms fashion these raw materials into intermediate goods. The number of unique items and processes in this category is enormous; a single car can have tens of thousands of parts. Average capital intensity is the lowest. Think sheet metal, hoses, simple plastic parts, clips, etc. The diversity in parts and low value added per step means that many firms in this space are small, with limited specialization or capital depth.

Many of these firms producing lower-volume parts are in glorified sheds without HVAC or decent lighting. They tend to have very low overhead because businesses can come and go, and they are often reliant on a small number of clients. Lead times depend on current workload, manual quoting velocity, ordering subcomponents, and the actual production processes. Timelines can stretch to months because each job waits for inputs to arrive and might require subcontracting at multiple shops.

Finished goods are the other end of the spectrum. Integrators design products, specify parts, and organize production. They have moderate capital intensity, and the number of unique items declines because parts combine into a product.

The Missing Middle

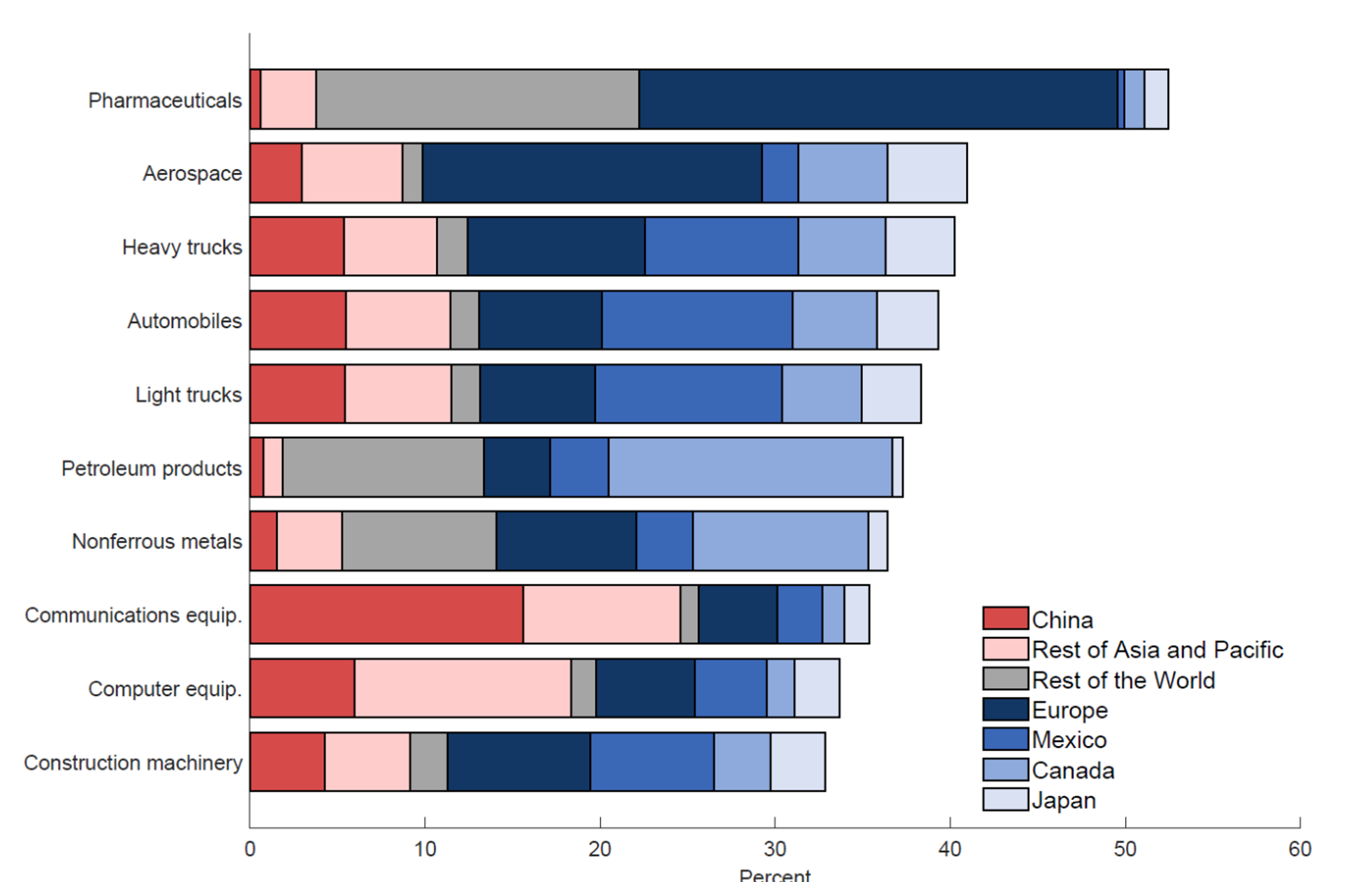

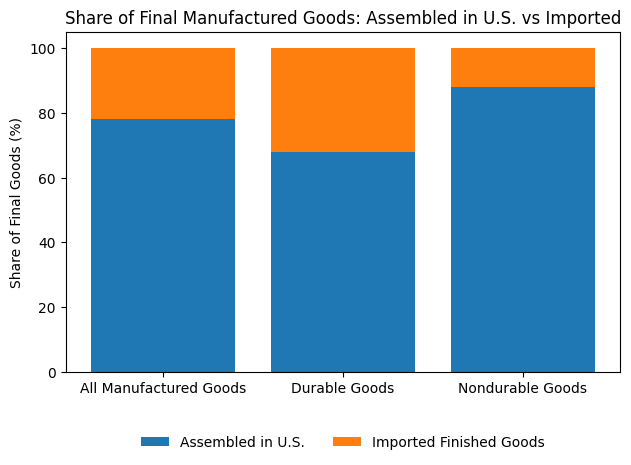

US competitiveness in intermediate and finished goods is a mixed bag based on volume. Supply chains tied to high-volume industries tend to perform better, for instance. Prototyping and similar low-volume activities are a struggle. Most assembly occurs in the US and includes imported parts that are inexpensive to ship. And of course, exports also contain both imported and domestically produced content.

The intermediate goods sector contains most of the value added in consumer and capital goods, and has the most leverage. The diversity and quality of subcomponents available determine what goods can be made (because not every firm can afford to integrate vertically). Most of the focus will be on this sector.

Import Share of Intermediate Inputs by Region of Origin, Selected U.S. Manufacturing Industries, 2019, Source: BEA and Federal Reserve

Most final products by value are assembled in the US. GPT-5 assembled BEA data for this graph.

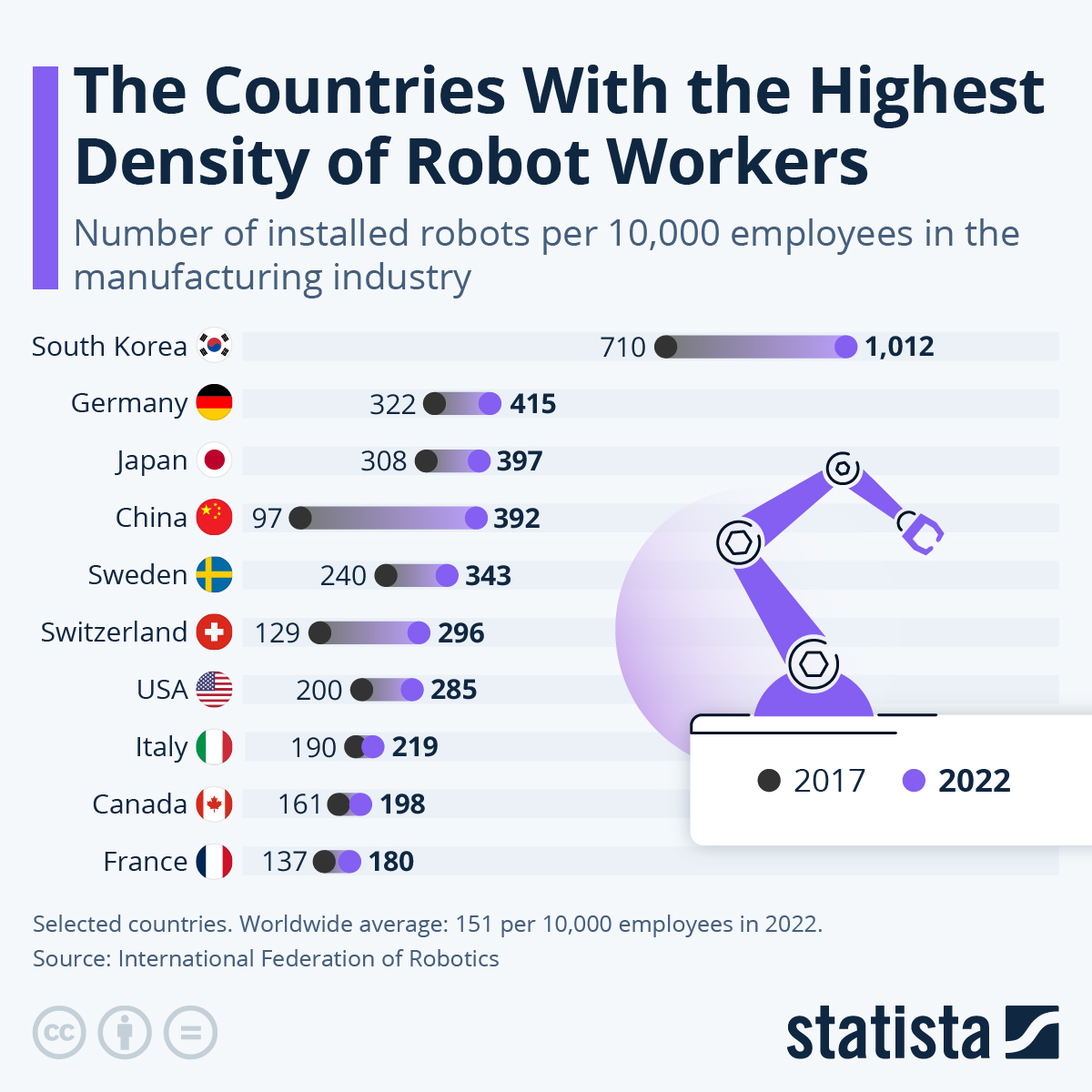

Case Study: Why Does the US Have so Few Robots Compared to China?

Many alarmists like to cite how many robots China is installing compared to the US. Chinese robot adoption has accelerated in the last decade. But this should be immediately puzzling to long-time followers of industrial automation. American companies have long over-automated, whether it is GM or Tesla, only to have to scale back due to high costs. China has much lower hourly wages, so how does it make sense for them to add so many robots?

Chinese robots on the rise.

The key is that robot arms are not labor-replacing, but labor-shifting. Robots decrease hourly labor while increasing labor demand for programmers, maintenance technicians, and skilled trades for installation. That labor cost usually dwarfs the upfront cost of the robot itself.

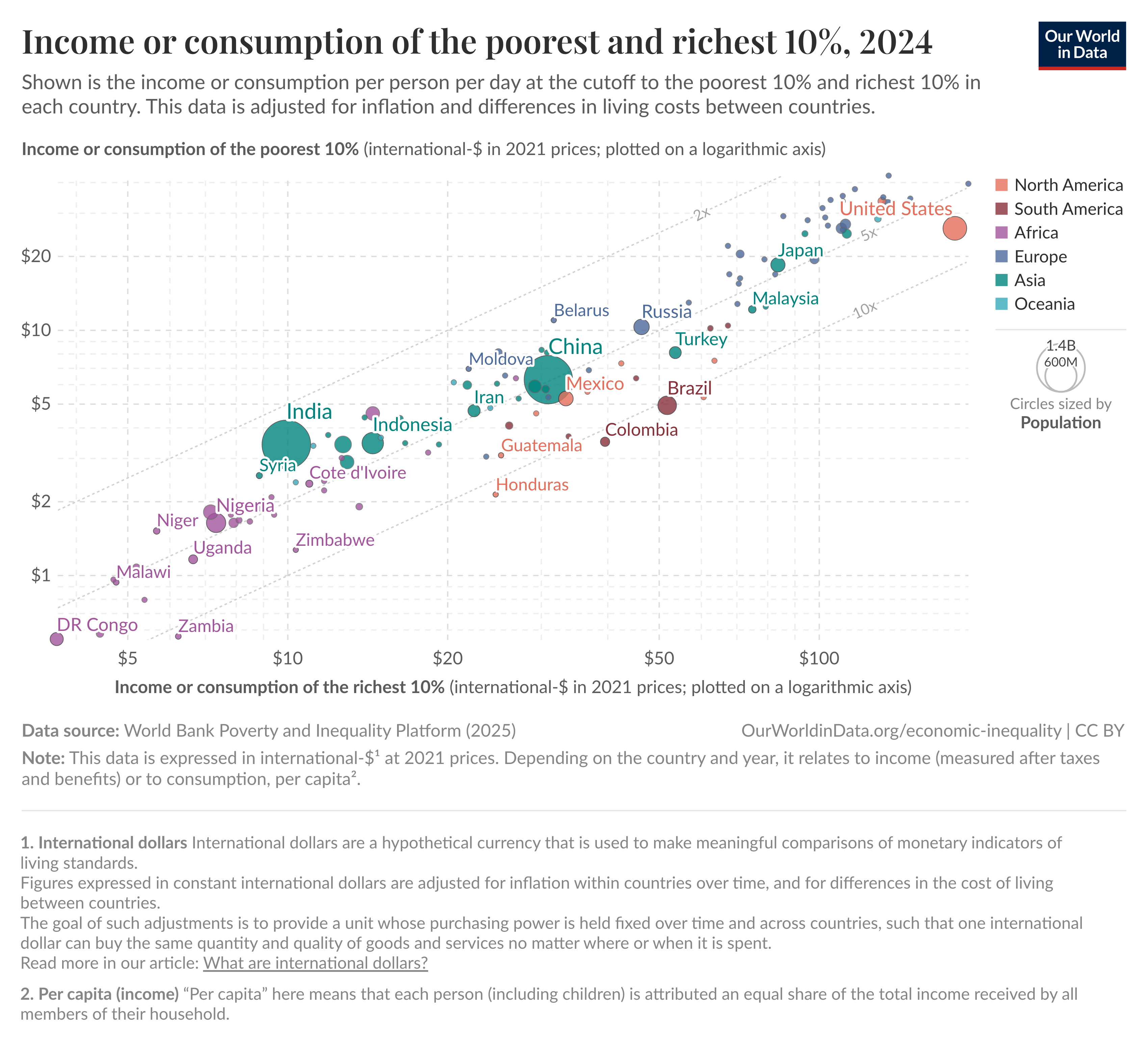

The US has a relative surplus of low-paid hourly workers and a shortage of high-skill workers, making a skilled-for-hourly replacement a poor trade in many cases. Our bottom 10% of workers earn roughly as much as those in other developed countries, even though US workers in the upper deciles perform much better than their international peers. Many less productive US manufacturing firms could buy a robot, but couldn't attract the talent to program it.

Exceptional top earners and middling low earners.

China has the opposite problem, making robots more attractive. It has a surplus of STEM graduates that are often underemployed, while "Hukou" residency restrictions complicate hiring hourly labor in coastal factories. Low-level robot programmers earn a fraction of the US wage, even at a much higher supply in absolute and per capita terms. These jobs are boring and require long stints away from home in relative backwaters to support factory retoolings. The alternative offers for those with programming skills in the US are much better.

Two key concepts come from this. First, high-end labor costs and availability are a challenge for US manufacturing. Second, technologies and market structure are contextual, where the US can't simply emulate China's manufacturing.

Finding Dynamism in Low-Volume Manufacturing

Low-volume manufacturing is important for new technologies, capital goods, and military applications. It traditionally suffers from both high costs and slow lead times. Modern buyers require much better performance.

The Inexorable Rise of Fixed Costs

Today's US firms have much higher fixed costs than in the past. Scale, specialization, increased high-end labor costs, and automation increase fixed costs.

Firms must be productive to cover these costs. High volumes of product are the obvious way. The other is a reduction in time. Any reduction in time to complete a task lowers its cost if expenditures are constant. The second mechanism is important for startups and other firms not focused on high-volume production, and these are the firms most critical for staying on the technological frontier.

When fixed costs are relatively high, the time it takes to receive a part and the fixed costs that accrue dwarf the list price. The item price does not accurately predict total cost. Ultra-short lead times are one of the most important features for buyers.

Speed Sells

America's existing manufacturing base, organized around volume, bulk, and lengthy product cycles, isn't positioned to provide speed and can be slower than Chinese producers who mass human resources to create speed, especially if the item is valuable enough to ship via air freight.

Productive time is a fraction of the total elapsed time for producing any low-volume part. Quoting, returning calls and emails, production queues, and other tasks create huge blocks of dead time. The low latency of software can eliminate dead time when end-to-end digitization removes humans from the customer procurement loop. Lead time can fall to days instead of weeks or months.

Customers will flock to extremely short lead times because of the value. Instant quotes, automatically converting customer files to production orders, and billing and shipping automation are ways to achieve this speed.

Eliminating Soft Costs

Clunky processes also impact the supply side. Soft costs and inefficient supervision are massive challenges for low-volume manufacturing. The office workers preparing the quote, the programmer laying out the job, the machine operator not set up to produce a good part on the first try, the billing department generating an invoice, and anyone else touching the process are the overwhelming sources of cost for small orders. There are hours of human labor in this process that don't involve any fabrication. The extra labor costs hundreds or thousands of dollars because of expensive US white collar labor, swamping the cost of small orders. Another way of saying it is that the "idiot index" is enormous - the steel in a steel part at low volume is only a few percent of the cost under the status quo.

The direct cost of labor, the worker making $25/hour to load and unload machines, is less of a burden. That is especially true when these workers operate within good setups that minimize waste.

The obvious solution is to, again, complete indirect tasks with software. Why is a human editing a spreadsheet and emailing it to create a quote? Why isn't the CNC machine getting autogenerated CAM instructions? Why is the billing manual? These are very solvable problems in 2026.

Startups that create internal automation to streamline the customer journey, slash lead times, and eliminate these soft costs improve buyer value by an order of magnitude and are amenable to venture capital-type bets. It is a software-heavy play with minimal technology risk. Unit marginal costs can fall to a fraction of the existing market. In fact, the pioneers in the sector are bootstrapped startups.

Instant Quotes and SendCutSend

The epitome of these ideas is the company SendCutSend. They began selling custom sheet metal parts in 2018 and now have a long list of services, including a rapidly growing CNC machining segment. The company has already exceeded $100 million in annual sales and is still growing quickly. Parts are affordable and get delivered in a few days. The prices and lead times are good enough that people often think they are a Chinese company. Other companies with similar services, like Osh Cut, have also grown at prodigious rates. Both of these companies are bootstrapped, with traditional equipment or bank loans being the only outside capital.

A prospective customer can upload the design of the part they want made, receive an immediate "yes/no" on whether the part is possible to produce, and a price and estimated delivery date. This step alone can save customers hours of effort and weeks of calendar time. Buying is as simple as hitting the button and plugging in a credit card (which can automate the payment backend). The customer file is processed to create the necessary programming for the required machines and finds an optimal place in the production queue to minimize material and labor usage. Other items, like shipping labels, are also generated and organized as needed.

Virtually all labor is now direct and limited to loading a sheet of metal into a laser cutting machine, removing the part from the cut sheet, or handling it for a few seconds to complete another operation, like bending, welding, or powder coating. A part might only have a few man-minutes of labor in it. SendCutSend has ~350 employees with yearly revenue per employee around $275,000. That exceeds many consumer-oriented food service and retail companies on the Fortune 500. The breakout success illuminates what is possible in other niches.

Car nuts modding their vehicles drove early demand for instant quote sheet metal parts.

Factors for Making Low-Volume Manufacturing Competitive in the US

Some key attributes make part suppliers more dynamic and responsive.

End-to-End Digitization

Knocking out soft costs and cutting lead times is the linchpin. The total customer cost of a part can decrease by an order of magnitude or more by eliminating these inefficiencies, leaving plenty of room for producer margins.

Machines are also often woefully underutilized due to slow setup times and poor production planning. Shops producing low-volume parts can have 10%-20% equipment utilization. An end-to-end digitized system can increase utilization to nearly 100%, improving return on capital.

Lightning Logistics

Historically, suppliers and job shops needed to be close to their customers unless they were shipping very high volumes of valuable parts. Each industrial town would have at least several shops. Logistics were expensive, and deliveries needed to be a short drive. Coordination was often low fidelity, too, making in-person visits valuable.

Proximity still helps, but modern semi trucks and parcel delivery services greatly increase the sales footprint of a shop by making small, fast deliveries affordable. Precise digital files make it easier to coordinate. I previously wrote a post about how autonomous cargo carriers and drones could improve these costs and delivery times by another order of magnitude.

Advancements in these areas could also reduce the amount of packaging needed. Today, packages have to survive careless humans, but a more robotized logistics network could guarantee gentle handling.

The reduction of soft costs paired with hyper-charged logistics will further shorten lead times and enable scale.

Collapsing Tooling Lead Time

"Hard tooling" refers to items such as molds and dies that enable ultra-high volume and inexpensive production of parts through methods like stamping, casting, and injection molding. The historical tradeoff has been that it can take months to create a die or mold. They are also expensive, requiring high volumes to justify the investment.

Instant quote, short lead time processes mostly avoid hard tooling because it is not flexible enough. Laser cutting and bending or roboforming can replace stamping. Casting molds and other tool and die can be 3D printed instead of machined. Many of these techniques are new (roboforming) or have seen dramatic improvement (laser cutting, 3D printing). Older processes, such as CNC machining, continue to improve and are more productive with CAM automation. Not only are low-volume runs more affordable, but these processes can also compete at higher volumes than possible before.

Avoiding hard tooling enables faster and cheaper prototyping, but it can also speed technology growth by shortening product cycles. Product cycles are necessarily long if it takes months or years to produce dies and molds. Production runs must be hundreds of thousands of parts to break even.

A wrinkle is that hard tooling itself is a production process dominated by skilled labor and soft costs, especially in the design and testing phase. A block of tool steel isn't that expensive, and it can often be machined into a mold or die within hours.

Software can generate the design and program the machines to produce hard tooling. New precision tool-less technologies can reduce the manual finishing time. Cost and cycle time decrease substantially.

The takeaway is that physical technology cycles can move much faster and improve across multiple dimensions when we reduce soft costs.

Circumventing Other Talent and Schedule Black Holes

There are many other tasks besides making parts. Detailed design, certifications, and construction management are viper nests of soft costs, almost by definition. Timelines can stretch to months or years, and visibility into the process is often poor. That applies to new electronic devices as much as the US Navy's ships.

Many of these areas are in such poor shape that startups are linking to existing physical providers and still able to offer substantial improvements. Over time, these firms should incorporate more end-to-end architectures to minimize lead time. For instance, it is revolting that hours worth of certification testing can have lead times of months at the typical Nationally Recognized Testing Labs.

Focus on Return on Investment, Not Robot Arms

People tend to have a visceral attraction to robot arms, especially in the context of reshoring production. It seems obvious that they are key. The point to remember is that they replace hourly labor with skilled labor, and that tradeoff isn't always worth it.

Attacking soft costs is almost always a better return on investment because results flow through to several categories: hourly labor becomes more efficient, lead times fall, skilled labor content decreases, equipment utilization improves, the customer base expands, and quality improves. The robot arm base case saves some hourly labor at the expense of adding more skilled labor, and can easily be negative if it needs reprogramming more than a few times per year. That is a problem when low-volume orders require new programming regularly. And from a practical standpoint, the soft costs need to be digitized first to feed the robot the correct information or reprogram it.

Automate is the last step in Elon's engineering algorithm, and it should really be more like 5a. "automate high ROI cognitive work" and 5b. "Add robot arm if it makes sense for the application." And in general, the robot arms aren't nearly as flexible in what they can do as humans, which is a disadvantage for facilities that have a lot of variation.

There are times when the robot arms do make sense. Some jobs are uncomfortable or dangerous. Robot arms can achieve more precision in many applications where that is valuable. Some items are too heavy for humans to move. It might be the same motion over and over. The point is to use the robot arms when they are really beneficial.

Of course, programming robot arms should improve through software automation. That still doesn't change the order of operations or discount the flexibility of human workers; it just increases robot arm productivity as automated programming technology improves.

Humanoid robots are also exciting, but are subject to the same considerations in a factory setting.

The Gravity Model at the Frontier

The US is the most attractive market for new high-end technologies and has the best innovation ecosystem. The market wants to create these technologies; the barrier is activation energy.

It seems clear that hardware entrepreneurs have (re)learned that iteration speed and hardware-rich development are a more effective way to create new things. Vertical integration is now the dominant solution in mind share. The downside is that it requires tens of millions of dollars and numerous highly skilled employees to kick off. It works for Elon, but not everyone has that skill set.

Amazon Web Services enabled software startups to begin without having to set up on-premises servers, lowering the activation energy. Instant quote, short lead time manufacturing companies and services can do the same for many hardware startups and tinkerers.

The emphasis on speed is because the model only works if the latency is low. The gravity model for frontier technology is much stronger than for existing products. Leading engineers become more productive, iteration cycles shorten, and new ideas become reality faster. Not only does fast service and lightning logistics help convert existing customers, but it also helps create the downstream manufacturers of tomorrow.

Competition, Structural Change, and Strategy

How will these new methods interact with the existing market structure?

Market Entry, Scale, and Competition

New intermediate firms, like SendCutSend, follow a typical pattern. The first entrant in a specific niche has a competitive advantage in pricing and lead time because removing soft costs drops the marginal part cost and fulfillment time. It earns attractive gross margins. Those margins support the higher fixed costs needed for expanding a digitized model. Growth sustains strong margins via fixed cost absorption and continued optimization.

More orders at the digitized shops tend to increase cash flow and investment because marginal costs are low and fixed costs are higher (compared to high marginal costs and low fixed costs for traditional shops). Software helps handle the complexity of scaling. Higher productivity means employees are paid better and can work in decent lighting and conditioned spaces, attracting and retaining quality ones. Equipment vendors are happy to extend financing to financially stable shops. Higher volume also makes customer orders less lumpy, making further investment in capacity less risky.

Scaling furthers savings in purchasing materials, justifies equipment or offerings that can expand the customer base, enables optimization of batches to minimize waste, and rationalizes long-tail software improvements.

The push towards instant quotes and short lead times is intense. Customers lose tolerance for multi-month lead times with multiple weeks for a quote. Existing firms that have already mastered this way of doing business can expand to new niches if new firms don't get there first. There are virtually endless niches available to exploit with new capabilities or by reorganizing existing ones.

Instant quotes are also another major force for consolidation because it isn't feasible to offer them unless most production steps are in control of the firm providing the quote. Loose networks of low-overhead job shops can't coordinate tightly enough.

If it isn't clear yet, the many existing small shops that don't leap will eventually close, with digitized firms absorbing their customers. The number of firms will decrease, customer surplus will skyrocket, and capital intensity will increase as the new, more productive firms can afford to invest and deepen capital.

Unlocking Capital Goods

Machines, robots, material carriers, and other capital goods are low-volume and labor-intensive. Efficient and flexible part suppliers make producing these lower-volume goods much more cost-effective with drastically shorter lead times. Lower-cost capital goods can make traditional volume production more cost-competitive and nimble, creating a flywheel of increasing demand and falling costs.

Why Not SaaS?

Why doesn't software as a service work for custom manufacturing?

One obvious answer is that a substantial portion of machine shops and small factories are still very analog, with some having no computers at all. These shops can be profitable (for now) due to low overhead costs and long-term customer relationships. Digital integration deeper than email and spreadsheets struggles to add value.

Manufacturing is also very unforgiving. The slightest error or variation can ruin a part. Glitches can cause downtime and are unacceptable. Success requires specific programming and might not generalize beyond a company's combination of machines, customers, and shop layout.

A general SaaS solution with days, weeks, or months of lag for fixes or new features that tries to absorb the reality from dozens or hundreds of shops is going to fail before even considering the customer acquisition cost. SendCutSend's codebase for linking ordering, queues, and machines is millions of lines of code and only considers the needs of one company.

Xeometry provides a quoting service for existing shops, but does not fully integrate into their systems and misses out on most of the efficiencies. The savings only materialize if you can fully digitize the pipeline to deliver instant quotes and very short lead times with very low soft costs.

If there are exceptions, it's likely in modular tasks that are challenging. But these firms can't shift the entire value proposition for a process alone; they are enablers.

Building software for one firm that becomes huge is more valuable than building it for many minnows that are hard to impact. Investors and founders missed the opportunity until recently because the perceived market size for individual manufacturing firms didn't account for dramatic consolidation and market expansion from short-lead time offerings.

The Impact of AI

Technology that makes writing software cheaper can be an accelerant when so much rides on reducing soft costs.

Early companies like SendCutSend and Osh Cut were in an area that was initially less software-intensive because laser cutting is easy to represent in two dimensions, and the market was accepting of simple cut parts without extra services.

Verticals such as machining, casting, welding, molding, printing, forming, or assembly require a lot more software horsepower. It is clear that AI-driven software development makes these applications much more practical to develop with small teams and has already helped newer startups substantially. These business models would be more difficult to start because of higher initial capital needs pre-Ai.

The net effect should be that traditional incumbents are in even more danger from startups. And once a digitized company starts the flywheel, its collection of hard-to-obtain data and other scale benefits will be hard to overcome.

Pattern Matching

We've established that these new-age industrials can become unicorns. Consolidation and manufacturing's big slice of GDP means there can be a lot more. Many opportunities only require software and do not have science/engineering risk. The companies become closer to what investors like with lower marginal costs and higher fixed costs that breed larger firms.

The opportunities tend to have these features:

-

Difficulty in Purchasing or Quoting at Low Volume

Serving small quantities is usually a money loser due to the office labor and opportunity cost to create designs and quotes. There is a long tail of customers who have no home. Even a very persistent effort might take weeks or months to get a quote.

-

Existing Firm Lead Times in Months

It is common to see lead times that are weeks or months, even though the work content might be minutes or hours. Approvals, design, purchasing, waiting for parts, waiting for other subcontractors, and correcting errors all stretch timelines.

-

Customers That Value Time

Any firm with highly skilled employees has high fixed costs. Long lead times balloon costs for these firms. Hobbyists can also value their time highly.

-

Fractured Market

Small quantity orders and high soft costs result in many small, inefficient suppliers. Their inability to meet the customer's needs creates a market opportunity.

-

Adjacent Markets

One narrow set of SKUs might be a good place to start. Future growth comes from expanding the market and eating nearby SKUs. It is a very Coasian growth strategy where software and scale lower internal transaction costs, allowing the firm to grow.

Then there are the common steps to take advantage of these opportunities:

-

Instant Quote and Feedback

Potential customers need answers right away. Can you make their part? What does it cost? And what is the lead time?. It is unacceptable to keep them waiting because it skyrockets costs for both parties.

-

One-Click Buying

Extra paperwork shouldn't be necessary. The customer forms, terms of use, and backend software can achieve the same goal as purchase orders and other traditional agreements. Eventually, larger buyers will catch on by automating their onboarding or risk becoming irrelevant.

-

Purchasing and Production Integration

Customer orders must link to a production planning queue. Software takes the details and creates work and routing instructions for humans and machines.

-

Keep Pushing Scale and Scope

Startups combine software, machines, and humans to expand offerings and scale, driving a virtuous cycle of falling marginal costs and fixed cost absorption.

Much of this functionality will be manual at first. Automation can scale with the business. Growth is necessary to gain scale advantages and to pay for the machines and software.

When it works correctly, a startup can find a good entry point that allows fast growth and early sales with a small capital base. Improvement pulls the ladder up, so it is much harder for incumbents to follow in their niche. Over time, founders and investors can eat more ambitious verticals as this pattern is better understood.

Policy Implications

The aims of policy should be to minimize high-end labor misallocation and enhance speed.

Minimizing Labor Allocation Distortion

Tariffs Constrain Labor and Hurt Demand

Accessing high-skilled labor is extremely important given how the US is short on high-end talent relative to the rest of the world.

Immigration is one way.

Imports are another. Tariffs make it more expensive for talented people who can't or won't immigrate to produce things for the US. Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Europe produce many of our low-volume goods, like machine tools. Capable engineers in these countries often make less than an elementary school teacher in the US.

The more straightforward issue with tariffs is that the US is strongest in basic materials and final assembly/design, while weaker in intermediates. These end manufacturers (new and old) are vulnerable to tariffs on their inputs and they are the buyers that the "speed strategy" is relevant for. Better supplier relationships, shorter lead times, and reductions in working capital are good reasons to reshore once nimble suppliers emerge. The healthier downstream companies are, the larger the potential market for new intermediate part and capital equipment producers. Zero tariffs are the best way to help them.

Tariffs and outright technology import bans also impact the US manufacturers' ability to import the best equipment and technology, making it harder for them to be competitive.

Industrial Policy Favors Labor Intensive Technology

Industrial policy for most products encourages skilled labor-intensive methods. The US exited these targets due to economic factors, not a lack of capability.

The CHIPS Act is an example of this, where the new fabs seem to work fine, but consume massive amounts of technical talent to build and operate. The chip industry's practice of "copying exactly" means they often avoid productivity-improving steps because they might impact yields.

The American way is for startups or firms like Tesla to refactor chip production processes, increasing total factor productivity. The CHIPS Act might still be a positive, but the cost is almost certainly many times the $50 billion price tag. The opportunity cost of allocating those labor resources is enormous, and many workers are learning methods that should be obsolete. Any firms working on the American way now have less relative funding and, more importantly, have stiffer competition for talent.

Government programs such as the Space Launch System are an example of projects that waste taxpayer money. They also exact unknowably high tolls by rubber-rooming tens of thousands of talented engineers.

Government involvement almost always wastes scarce human capital resources.

Raw Material Production Demands High Productivity

Raw materials such as steel have always been a focus for those interested in communism and industrial policy. Even so, the scale of basic materials means the US performs well. We are leaders or proficient in oil and gas, coal, agricultural commodities, cement, sand/aggregate, steel, aluminum, wood products, fertilizer, and high-volume chemical commodities.

Surprise, surprise, the US produces fewer basic materials that have small markets and relatively complex processing steps (making them skilled labor-intensive). The global rare earth market is less than $5 billion per year, for instance. Many of these other random materials are even less. The amount of high-end human capital cycles spent recently on these tiny markets is a tragedy.

The solution is simple for small markets - stockpiles (which it appears the USG might be taking more seriously). If other countries want to sell below cost, then we should store several years of supply in a warehouse. A few hours of the national security budget and ~20,000 square feet of warehouse should suffice for a rare earth feedstock/product stockpile, for instance. Stockpiles provide insurance while conserving our valuable labor. There is time to redirect resources to production if things go south.

America's innovation in basic materials is also unappreciated. Fracking is the most obvious. Steel has also been impressive. The US commercialized the electric arc furnace (EAF) and continues to push which alloys and products EAFs can produce without primary steel.

New technology utilizes computer vision to sort aluminum. Millions of tons of aluminum scrap that are exported or landfilled can be recycled each year instead.

Magnets are another interesting area (~80% of the market value of rare earths is for magnets). Clever motor designs can use iron ferrite magnets instead of rare earths for many applications, and a process to produce high-performance iron nitride magnets is reaching commercial scale.

The common thread between these basic materials technology successes is that they all markedly increase total factor productivity by minimizing labor, efficiently using inputs, and reducing capital intensity. Why build a multi-billion-dollar primary aluminum facility when a sorting plant is a fraction of the cost and faster to build? The market has a preference. EAF steel, recycled aluminum, and non-rare-earth magnets are all seeing expansion in the US.

Capital Intensive Equals Labor Intensive

I often see capital cost comparisons across time and space with the expectation that the lowest cost should be attainable everywhere. Even less-regulated oil and gas drilling can have 2x-3x cost differences between active basins that are only a few hundred miles apart. Drilling in areas without consistent activity can be 5x more.

Ultimately, these capital-intensive endeavors are complex construction projects that are massively labor-intensive and lack permanent learning curves. Local labor rates, supplier bases, and firm organization have huge impacts on cost.

Natural variation in capital costs means naive policies to encourage certain technologies in hopes of reaching the costs of Country X or the US in past year Y are often misguided. The US is so rich that we need different technologies than the rest of the world to increase output, specifically ones that conserve high-end labor. Comparisons to other countries or the past US do not account for the value of our top workers today. That misunderstanding can lead to the horrific destruction of capital.

Capital Markets Conserve Labor

Capital allocation is not perfect, but the US has the most liquid, efficient, and risk-taking capital markets that humans have ever known. We also have the best compensated human capital in the history of mankind. Finding new ways to reduce high-end labor intensity is incredibly profitable and can be funded, especially once the opportunities are more legible. The majority of complaints about funding are for low-productivity processes or concepts.

Removing Regulatory Speed Bumps

Regulatory time burdens match slow lead times as a productivity killer.

Leading Edge Tech Barriers

The scariest kind of barrier is bans in critical industries. The FAA's effective over-the-horizon drone ban is example 1A, which is only slowly being corrected with waivers and new rules.

Policies like this could end the American project by crippling our defense and technological development. Other critical areas include aerospace, AI, and submarine development.

Built-in Stagnation

A subset of these industry regulations is the assumption that designs change slowly because of massive investments in design and tooling. That will become less and less true as efficient low-volume manufacturing ramps and hard tooling costs decrease. NTSHA, FAA, UL, NEMA, ASME, etc. will need to adjust to allow "by right" approvals, encourage self-certification, or approve designs quicker.

Many of these certifications require testing to ensure product safety, but the tests themselves often take hours, while approvals take months or years of calendar time. Other areas, like environmental review or permits, are mostly dead time. There is a massive scope to reduce calendar time without even altering testing protocols.

Many other areas of red tape are not directly threatening, but have indirect costs. If it takes many extra smart people to build projects or if restrictions keep AI from improving the productivity of top-tier labor, then that labor isn't available elsewhere.

It is pure insanity that people spend any political capital or effort on direct industrial policy that will likely decrease total output instead of focusing on regulations holding back drones, aircraft, permitting, and other technologies.

Expanding Production Possibilities

The policy summary is that we have a shortage of skilled labor. We must heed the production possibilities frontier. Finding ways to reduce skilled labor content in processes through direct automation or lead time reduction generates cash and allows the US to produce more goods and services. Regulatory requirements that make our top workers less productive hurt what we can produce, and can be fatal. Industrial policy almost inevitably consumes more skilled labor and reduces what we can produce.

National Security Requirements

It is the early 1950s. America accounts for more than half of global manufacturing output. The country still basks in the glory of its World War II victory. Pax Americana.

Yet one story from the Korean War is illustrative. Following the North Korean Army's collapse in late 1950, the Russians sent their new MIG-15 fighters. The MIG was superior to any US/UN aircraft in the theater, and quickly racked up kills.

A critical mission for US airpower was to bomb bridges, rail, and depots near the Chinese border to prevent enemy troops and supplies from reaching the front lines. Losses of bombers became so severe that the US Air Force stopped long-range bombing for months in the spring of 1951 (even though it was a critical point in the war where lines were still fluid). When bombing resumed, missions were at night, drastically reducing effectiveness.

The Air Force deployed the F-86 to help counter the MIG threat, but early war versions were still at a disadvantage. There is some debate about the kill-to-loss ratio, but it is indisputable that the F-86 could not achieve air supremacy and reopen daylight deep strikes. That led to many more US casualties and played a part in a subpar treaty. The US is lucky that the Russians were reluctant to fly the MIG-15 near the US/UN lines. That allowed uninterrupted US close air support and unhindered supply lines.

Lessons

Only a few short years after WWII, the US had given up the technical edge in the most important conventional military technology and suffered greatly in Korea. We could have produced tens of thousands of P-51s or P-80s, but the losses would have been unacceptable. Having by far the best manufacturing base only bought the option to increase casualties and shrink the civilian economy at home.

What might an alternative have looked like?

-

The Navy and Air Force struggled to hit key bridges and rail targets in the first place, and barely damaged them when they did. Guided bombs have a much better impact with a fraction of the sorties. The Germans had a very effective radio-guided anti-ship bomb in World War II that could have worked. A critical aspect of this would be the ability to update control frequencies to avoid jamming.

-

A superior fighter could have maintained air supremacy over North Korea, allowing much more aggressive attacks on supply chains. Faster development cycles and more realistic testing were necessary.

-

Better commanders would have helped, too. A late 1950 rout leading to an attritional slugfest was not an optimal strategy. Nor was the Pentagon's obsession with A-bombs and H-bombs that left other weapons development rotting on the vine.

Would these changes have altered the Korean War? There is no way to know, but almost certainly, many fewer US troops would have died. They would also decrease the amount of war goods needed. Higher productivity weapons allow the US to maintain hegemony even in "peacetime."

In Korea, the US needed faster cycle time and better technology in munitions, fighter aircraft, and leadership, more than mass production.

Maintaining Technological Supremacy

There is an old saying that "A big Soviet Army beats a small Soviet Army." There is no world where the US, with a small fraction of the global population, can dominate without techno-economic superiority. Thankfully, it has been the norm since the Industrial Revolution that the global power has a small share of the population. Technology provides so much leverage that it is almost inevitable.

There are several relevant observations:

-

East Asia and the Pacific are the most important theaters for the US. The long distances mean small battery drones are limited in capability (I cover what they can do in my "Drone Air Force" post). Ultimately, high-performance aircraft and submarines powered by jet engines and nuclear reactors will deliver the mass-produced munitions.

-

The US could increase capacity to produce Virginia-class submarines by 5x, but a single flaw that makes them detectable would mean the effort was a complete waste. Mass production is a net negative without the technological edge in most domains.

-

There is a consensus that the US produces its weapon platforms in too small quantities. 1-2 submarines or destroyers, a few bombers, and 100+ F-35s per year. An adjustment would be producing dozens or low hundreds of ships and thousands of large aircraft. These numbers are still orders of magnitude away from mass production volumes. Plus, designs need constant updating, and lot sizes would be even smaller.

-

Items that require mass production, like shells, rockets, bombs, missiles, military-grade explosives, or FPV drones, are rarely dual-use. The investment in factories is also a small portion of the current military budget. The answer is to build extra capacity "just in case" rather than a general industrial policy program that won't be relevant for mass-produced weapons.

-

The world is much richer and global trade flows are much larger than in the 1940s. US Steel production exceeds 1945 numbers. Today's commercial ship fleet is more than an order of magnitude greater than what the US needed in World War II. The Navy could capture Chinese-flagged ships outside of East Asia and have more than enough merchant marine capacity to prosecute a war. A country like South Korea produces more shipping in one year than the US did in the entire Second World War.

-

US steel production is over 100 million tons per year. That is enough to build something like 1200 aircraft carriers or 15,000 destroyers per year. Modern warships are ~80% crew accommodations, so autonomous ships would use a fraction of the resources, yet. The US might even be able to build 1 billion FPV drones per year with existing capacity.

-

Humans are still the constraint in drone warfare. Both Russia and Ukraine have more drones than trained operators. One side can easily outproduce the other in drones and have lower combat power if the opposition trains more pilots or uses software to augment or replace them.

The modern world is so bountiful that mass production is no longer the limiting factor. What is in short supply is the talent needed to equip and operate the armed forces. Attempts to influence and centralize weapons development or production will almost certainly reduce US combat effectiveness by misallocating this talent. Those advocating for more free-market procurement are on the right track.

Efforts to increase the flexibility of factories and reduce the skilled labor content in production will make the US much more capable, even if the US doesn't dominate the manufacturing market share.

Flexibility and elite human capital efficiency are the keys to victory.

The China Question and US Allies

China is the elephant in the room for many worried about manufacturing and technology. In a world where the US has a flexible production system and remains on the frontier, we shouldn't need to worry about China much at all.

The US could adjust to any supply disruptions or military threats using the newfound flexibility.

China would still be a large manufacturer because of its size and the constraints of specialization, economies of scale, and the gravity model. But the US would not be dependent.

Ideas are non-rival goods that benefit any adopter. China will produce ideas that help the world, and the US can rapidly adopt them, even if the US's idea output is still greater.

The US should continue to encourage Japan, Europe, and South Korea to make their economies and societies more flexible. They can better participate and generate new technology instead of stagnating.

Fundamentally, the larger the network, the richer we all will be, and there is no reason why the US should not continue to be the center of it as the opportunity grows for our best workers to become even more productive.

The Bootstrapping of a Manufacturing Giant

The lack of flexibility in the current American manufacturing system is a source of pain and weakness.

Many industries have increased productivity and made high-end workers more valuable, while lower-volume manufacturing has not.

There are now many low-volume niches where internal software can increase productivity.

Even more importantly, lead times and customer hours spent on procurement will decrease substantially. That makes every engineer at product-level companies more productive. It can eventually enable many new products, such as low-volume machine tools and automation, that further add to gains.

Cycle times for products can decrease, improving the pace of technological development. Changes in cycle time make it critical that regulations move away from assumptions based on inflexible mass production and "model year" upgrades.

Progress can go forward without government support. The key is for more entrepreneurs and financiers to understand the pattern of value creation that results from reducing soft costs and crashing lead time. It has taken me several months to research and write this post, and the shift in mood and ideas towards this outcome is noticeable just in that time period.

Funding Opportunities Appendix

I stumbled into investing in several of these companies(*) while writing this post. Several high-quality investors writing larger checks, usually a few hundred thousand dollars but sometimes more, followed. If you have a new or existing startup that meets the criteria and you are interested in an investment from me and follow-on investors, feel free to fill out this Google form. The form is necessary to allow me to answer quickly without using much of my time.

Here is a non-exhaustive list of companies I think embody these ideas:

Forge Automation - Instant quote 5-axis CNC machining with a focus on soft cost reduction/automation.

NOX Metals - Instant quote metals supplier to shorten lead times, reduce metal costs, and minimize waste.

Blitz Panel* - Instant quote electrical panels.

Fab Works - Instant quote sheet metal, tubes, and welding.

RMFG* - Instant Quote sheet metal and welding.

Digital Metal* - Instant quote cast metal parts with 3d printed molds.

Obie Industries* - Instant quote formed sheet metal parts via 3d printed tool and die.

ASAP PCB - Instant quote and quick turn printed circuit boards.

Osh Cut - Instant quote sheet metal and dozens of related processes.

SendCutSend - Instant quote sheet metal and dozens of related processes.

And some that are exciting but have not (yet) embraced the full permissionless end-to-end model:

Diode Computers - Automated design and supplier integration for printed circuit boards.

Unlimited Industries - AI-enabled engineering, procurement, and construction to shorten construction cycles and reduce cost/schedule overrun risk by doing full detail design before construction.

Bot Built - Accurate material lists from PDF architecture drawings.

Senra Systems - Custom wire harnesses with shorter lead times.

Atomic Industries - Automating design and testing of injection molding dies.

Dirac - Automated assembly work instructions.

Hadrian - Highly digitized CNC machining for large defense contractors.

Normal Factory - Automating regulatory certification and compliance.

Machina - "Stamped" sheet metal parts without hard tooling with "roboforming."

Podium Automation - Quick-turn electrical panels.

Speed Can Reindustrialize America

2026 February 12 Twitter Substack See all postsReviving manufacturing doesn't require a planned economy, just a better business model. Thanks to Patrick Collison for providing helpful feedback on this post.

Manufacturing and the US Economy

The US manufacturing sector is ~10% of GDP (~$3 trillion), and the US is the second-largest manufacturing country. Yet many see the US as a manufacturing failure and prefer extremely blunt government-directed policies.

I think the underlying causes of this malaise are both misunderstood and misdiagnosed. The US excels at high-volume manufacturing, but not low-volume manufacturing. The US can revive low-volume manufacturing with markets and technology once we understand the issue. The following are the main points:

The US does a lot of manufacturing, but it's tilted towards high-volume, static, and boring products.

The US performs poorly in producing short lead time, custom parts.

Long lead times and soft costs, fueled by the world-leading US wages for "white collar" work, are the root cause of poor performance in low-volume production because there are few units to spread the soft costs over.

The same world-leading wages create massive demand for short lead time parts.

New end-to-end digitized manufacturers, some already reaching unicorn territory, eliminate almost all soft costs and drastically shorten lead times with instant quoting and production-integrated software.

The number of intermediate manufacturing companies will consolidate drastically because the digitized value structure is superior, leading to much larger firm size, and making these companies great investments.

AI is an accelerant for these startups.

Flexible and affordable low-volume production makes military procurement and production of capital goods more efficient.

Almost all active policies make things worse by misallocating talent. The focus should be on reducing calendar time for various government approvals and certifications.

Flexible manufacturing keeps the US on the technology frontier and resilient to supply shocks, making China less of a concern.

The sum is that physical technology cycles can go much faster once these new business models permeate the economy.

Understanding the Manufacturing Industry Today

Why Do Manufacturers Exist?

The rhetoric about manufacturing can lose sight of the core organizing principles. Why doesn't one country produce all the manufactured goods? Why are there multiple factories or only one factory for certain goods? Why doesn't every home produce its own steel?

There are three main forces at work:

Specialization

Manufacturing is complex and competitive. It pays to specialize. The cornucopia of human desires and variation in conditions is so great that no single region can dominate everything. There aren't enough people and resources to collect the near infinite amount of knowledge needed.

Economies/Diseconomies of Scale

Most manufacturing reaches diseconomies of scale before global saturation. Then the rational thing to do is distribute the facilities to minimize transportation and other costs. Cars, gasoline, lumber, and cement are examples of products usually produced and consumed regionally. Other products, like concrete, sand, or certain types of light manufacturing, have local markets.

There are a few product categories with slowly diminishing returns to scale and very low shipping and localization costs, pushing them towards global production. Flat screen TVs, computer chips, ships, and phones are this way.

The Gravity Model

Most economic transactions occur between parties near each other. Transaction density decreases rapidly with distance. These models can be so accurate that they've discovered lost ancient cities.

The reasoning for gravity models is friction from transportation costs, transit time, cultural/language differences, and human relationships. It is easier and cheaper to get deals done close to home. But a few items are so scarce that it is worth the distance.

Even if one country is superior at production at the factory level, other costs mean it usually cannot dominate the market.

The net result is that most products are produced near buyers, even if there are other costs and productivity differentials. Richer countries substitute more capital for labor because of higher labor costs.

US Manufacturing's Hollowness

A few attributes stand out for the most economical products to produce in the US. These match what we'd expect from the gravity model, specialization, and economies of scale.

High Transportation Costs

Items like sand or cement, where transportation is a high portion of cost, tend to be domestically produced. Same for bulkier items like cars, dishwashers, etc.

Needs Speed to Market

Perishable items or other time-sensitive applications can get boosted.

High Volume for Fixed Cost Absorption

Any manufacturing process or run requires some setup or tooling. The work can include programming robots, organizing processes, designing molds or dies, among other activities.

The simplest way to reduce the setup burden is to produce high quantities of the item, spreading setup costs over many units.

Long Product Lifecycles

Static designs can often remain in the US because retooling and new equipment are rare. Or the firm can safely invest in automation, knowing it will have ample time/quantity to pay off.

Technological Complexity

Some technologies are challenging to manufacture, and US firms are among the world leaders. Drilling rigs, PDC bits, frac fleets, gas turbines, combines, sprayers, stealth fighters, and commercial aircraft are a few examples. Development cycles are long and R+D is significant.

Amenable to Mechanization and/or Automation

Some processes are easier to automate or mechanize than others. Chemical processing is an example of a process that is easier to automate, and the US is strong in (low feedstock costs also help).

Almost all the forces push US manufacturing towards high-volume, static, bulky stuff.

Low-volume products are not profitable for the majority of US manufacturers. More dynamic US manufacturing requires economical production at lower volumes.

The Structure of the US Manufacturing Industry

Layers of firms handle physical production. There is a spectrum from raw materials to final goods.

There are relatively few raw materials, like steel or plastic. The scale is massive since they serve many markets. The scale, sales volume, and commodity nature drive production to happen in gargantuan, capital-intensive facilities. The table below shows the US is almost self-sufficient in high volume basic items and the exceptions are where Canada has especially good resources.

High volume, cheap materials favor domestic production. Source: GPT-5

Firms fashion these raw materials into intermediate goods. The number of unique items and processes in this category is enormous; a single car can have tens of thousands of parts. Average capital intensity is the lowest. Think sheet metal, hoses, simple plastic parts, clips, etc. The diversity in parts and low value added per step means that many firms in this space are small, with limited specialization or capital depth.

Many of these firms producing lower-volume parts are in glorified sheds without HVAC or decent lighting. They tend to have very low overhead because businesses can come and go, and they are often reliant on a small number of clients. Lead times depend on current workload, manual quoting velocity, ordering subcomponents, and the actual production processes. Timelines can stretch to months because each job waits for inputs to arrive and might require subcontracting at multiple shops.

Finished goods are the other end of the spectrum. Integrators design products, specify parts, and organize production. They have moderate capital intensity, and the number of unique items declines because parts combine into a product.

The Missing Middle

US competitiveness in intermediate and finished goods is a mixed bag based on volume. Supply chains tied to high-volume industries tend to perform better, for instance. Prototyping and similar low-volume activities are a struggle. Most assembly occurs in the US and includes imported parts that are inexpensive to ship. And of course, exports also contain both imported and domestically produced content.

The intermediate goods sector contains most of the value added in consumer and capital goods, and has the most leverage. The diversity and quality of subcomponents available determine what goods can be made (because not every firm can afford to integrate vertically). Most of the focus will be on this sector.

Import Share of Intermediate Inputs by Region of Origin, Selected U.S. Manufacturing Industries, 2019, Source: BEA and Federal Reserve

Most final products by value are assembled in the US. GPT-5 assembled BEA data for this graph.

Case Study: Why Does the US Have so Few Robots Compared to China?

Many alarmists like to cite how many robots China is installing compared to the US. Chinese robot adoption has accelerated in the last decade. But this should be immediately puzzling to long-time followers of industrial automation. American companies have long over-automated, whether it is GM or Tesla, only to have to scale back due to high costs. China has much lower hourly wages, so how does it make sense for them to add so many robots?

Chinese robots on the rise.

The key is that robot arms are not labor-replacing, but labor-shifting. Robots decrease hourly labor while increasing labor demand for programmers, maintenance technicians, and skilled trades for installation. That labor cost usually dwarfs the upfront cost of the robot itself.

The US has a relative surplus of low-paid hourly workers and a shortage of high-skill workers, making a skilled-for-hourly replacement a poor trade in many cases. Our bottom 10% of workers earn roughly as much as those in other developed countries, even though US workers in the upper deciles perform much better than their international peers. Many less productive US manufacturing firms could buy a robot, but couldn't attract the talent to program it.

Exceptional top earners and middling low earners.

China has the opposite problem, making robots more attractive. It has a surplus of STEM graduates that are often underemployed, while "Hukou" residency restrictions complicate hiring hourly labor in coastal factories. Low-level robot programmers earn a fraction of the US wage, even at a much higher supply in absolute and per capita terms. These jobs are boring and require long stints away from home in relative backwaters to support factory retoolings. The alternative offers for those with programming skills in the US are much better.

Two key concepts come from this. First, high-end labor costs and availability are a challenge for US manufacturing. Second, technologies and market structure are contextual, where the US can't simply emulate China's manufacturing.

Finding Dynamism in Low-Volume Manufacturing

Low-volume manufacturing is important for new technologies, capital goods, and military applications. It traditionally suffers from both high costs and slow lead times. Modern buyers require much better performance.

The Inexorable Rise of Fixed Costs

Today's US firms have much higher fixed costs than in the past. Scale, specialization, increased high-end labor costs, and automation increase fixed costs.

Firms must be productive to cover these costs. High volumes of product are the obvious way. The other is a reduction in time. Any reduction in time to complete a task lowers its cost if expenditures are constant. The second mechanism is important for startups and other firms not focused on high-volume production, and these are the firms most critical for staying on the technological frontier.

When fixed costs are relatively high, the time it takes to receive a part and the fixed costs that accrue dwarf the list price. The item price does not accurately predict total cost. Ultra-short lead times are one of the most important features for buyers.

Speed Sells

America's existing manufacturing base, organized around volume, bulk, and lengthy product cycles, isn't positioned to provide speed and can be slower than Chinese producers who mass human resources to create speed, especially if the item is valuable enough to ship via air freight.

Productive time is a fraction of the total elapsed time for producing any low-volume part. Quoting, returning calls and emails, production queues, and other tasks create huge blocks of dead time. The low latency of software can eliminate dead time when end-to-end digitization removes humans from the customer procurement loop. Lead time can fall to days instead of weeks or months.

Customers will flock to extremely short lead times because of the value. Instant quotes, automatically converting customer files to production orders, and billing and shipping automation are ways to achieve this speed.

Eliminating Soft Costs

Clunky processes also impact the supply side. Soft costs and inefficient supervision are massive challenges for low-volume manufacturing. The office workers preparing the quote, the programmer laying out the job, the machine operator not set up to produce a good part on the first try, the billing department generating an invoice, and anyone else touching the process are the overwhelming sources of cost for small orders. There are hours of human labor in this process that don't involve any fabrication. The extra labor costs hundreds or thousands of dollars because of expensive US white collar labor, swamping the cost of small orders. Another way of saying it is that the "idiot index" is enormous - the steel in a steel part at low volume is only a few percent of the cost under the status quo.

The direct cost of labor, the worker making $25/hour to load and unload machines, is less of a burden. That is especially true when these workers operate within good setups that minimize waste.

The obvious solution is to, again, complete indirect tasks with software. Why is a human editing a spreadsheet and emailing it to create a quote? Why isn't the CNC machine getting autogenerated CAM instructions? Why is the billing manual? These are very solvable problems in 2026.

Startups that create internal automation to streamline the customer journey, slash lead times, and eliminate these soft costs improve buyer value by an order of magnitude and are amenable to venture capital-type bets. It is a software-heavy play with minimal technology risk. Unit marginal costs can fall to a fraction of the existing market. In fact, the pioneers in the sector are bootstrapped startups.

Instant Quotes and SendCutSend

The epitome of these ideas is the company SendCutSend. They began selling custom sheet metal parts in 2018 and now have a long list of services, including a rapidly growing CNC machining segment. The company has already exceeded $100 million in annual sales and is still growing quickly. Parts are affordable and get delivered in a few days. The prices and lead times are good enough that people often think they are a Chinese company. Other companies with similar services, like Osh Cut, have also grown at prodigious rates. Both of these companies are bootstrapped, with traditional equipment or bank loans being the only outside capital.

A prospective customer can upload the design of the part they want made, receive an immediate "yes/no" on whether the part is possible to produce, and a price and estimated delivery date. This step alone can save customers hours of effort and weeks of calendar time. Buying is as simple as hitting the button and plugging in a credit card (which can automate the payment backend). The customer file is processed to create the necessary programming for the required machines and finds an optimal place in the production queue to minimize material and labor usage. Other items, like shipping labels, are also generated and organized as needed.

Virtually all labor is now direct and limited to loading a sheet of metal into a laser cutting machine, removing the part from the cut sheet, or handling it for a few seconds to complete another operation, like bending, welding, or powder coating. A part might only have a few man-minutes of labor in it. SendCutSend has ~350 employees with yearly revenue per employee around $275,000. That exceeds many consumer-oriented food service and retail companies on the Fortune 500. The breakout success illuminates what is possible in other niches.

Car nuts modding their vehicles drove early demand for instant quote sheet metal parts.

Factors for Making Low-Volume Manufacturing Competitive in the US

Some key attributes make part suppliers more dynamic and responsive.

End-to-End Digitization

Knocking out soft costs and cutting lead times is the linchpin. The total customer cost of a part can decrease by an order of magnitude or more by eliminating these inefficiencies, leaving plenty of room for producer margins.

Machines are also often woefully underutilized due to slow setup times and poor production planning. Shops producing low-volume parts can have 10%-20% equipment utilization. An end-to-end digitized system can increase utilization to nearly 100%, improving return on capital.

Lightning Logistics

Historically, suppliers and job shops needed to be close to their customers unless they were shipping very high volumes of valuable parts. Each industrial town would have at least several shops. Logistics were expensive, and deliveries needed to be a short drive. Coordination was often low fidelity, too, making in-person visits valuable.

Proximity still helps, but modern semi trucks and parcel delivery services greatly increase the sales footprint of a shop by making small, fast deliveries affordable. Precise digital files make it easier to coordinate. I previously wrote a post about how autonomous cargo carriers and drones could improve these costs and delivery times by another order of magnitude.

Advancements in these areas could also reduce the amount of packaging needed. Today, packages have to survive careless humans, but a more robotized logistics network could guarantee gentle handling.

The reduction of soft costs paired with hyper-charged logistics will further shorten lead times and enable scale.

Collapsing Tooling Lead Time

"Hard tooling" refers to items such as molds and dies that enable ultra-high volume and inexpensive production of parts through methods like stamping, casting, and injection molding. The historical tradeoff has been that it can take months to create a die or mold. They are also expensive, requiring high volumes to justify the investment.

Instant quote, short lead time processes mostly avoid hard tooling because it is not flexible enough. Laser cutting and bending or roboforming can replace stamping. Casting molds and other tool and die can be 3D printed instead of machined. Many of these techniques are new (roboforming) or have seen dramatic improvement (laser cutting, 3D printing). Older processes, such as CNC machining, continue to improve and are more productive with CAM automation. Not only are low-volume runs more affordable, but these processes can also compete at higher volumes than possible before.

Avoiding hard tooling enables faster and cheaper prototyping, but it can also speed technology growth by shortening product cycles. Product cycles are necessarily long if it takes months or years to produce dies and molds. Production runs must be hundreds of thousands of parts to break even.

A wrinkle is that hard tooling itself is a production process dominated by skilled labor and soft costs, especially in the design and testing phase. A block of tool steel isn't that expensive, and it can often be machined into a mold or die within hours.

Software can generate the design and program the machines to produce hard tooling. New precision tool-less technologies can reduce the manual finishing time. Cost and cycle time decrease substantially.

The takeaway is that physical technology cycles can move much faster and improve across multiple dimensions when we reduce soft costs.

Circumventing Other Talent and Schedule Black Holes

There are many other tasks besides making parts. Detailed design, certifications, and construction management are viper nests of soft costs, almost by definition. Timelines can stretch to months or years, and visibility into the process is often poor. That applies to new electronic devices as much as the US Navy's ships.

Many of these areas are in such poor shape that startups are linking to existing physical providers and still able to offer substantial improvements. Over time, these firms should incorporate more end-to-end architectures to minimize lead time. For instance, it is revolting that hours worth of certification testing can have lead times of months at the typical Nationally Recognized Testing Labs.

Focus on Return on Investment, Not Robot Arms

People tend to have a visceral attraction to robot arms, especially in the context of reshoring production. It seems obvious that they are key. The point to remember is that they replace hourly labor with skilled labor, and that tradeoff isn't always worth it.

Attacking soft costs is almost always a better return on investment because results flow through to several categories: hourly labor becomes more efficient, lead times fall, skilled labor content decreases, equipment utilization improves, the customer base expands, and quality improves. The robot arm base case saves some hourly labor at the expense of adding more skilled labor, and can easily be negative if it needs reprogramming more than a few times per year. That is a problem when low-volume orders require new programming regularly. And from a practical standpoint, the soft costs need to be digitized first to feed the robot the correct information or reprogram it.

Automate is the last step in Elon's engineering algorithm, and it should really be more like 5a. "automate high ROI cognitive work" and 5b. "Add robot arm if it makes sense for the application." And in general, the robot arms aren't nearly as flexible in what they can do as humans, which is a disadvantage for facilities that have a lot of variation.

There are times when the robot arms do make sense. Some jobs are uncomfortable or dangerous. Robot arms can achieve more precision in many applications where that is valuable. Some items are too heavy for humans to move. It might be the same motion over and over. The point is to use the robot arms when they are really beneficial.

Of course, programming robot arms should improve through software automation. That still doesn't change the order of operations or discount the flexibility of human workers; it just increases robot arm productivity as automated programming technology improves.

Humanoid robots are also exciting, but are subject to the same considerations in a factory setting.

The Gravity Model at the Frontier

The US is the most attractive market for new high-end technologies and has the best innovation ecosystem. The market wants to create these technologies; the barrier is activation energy.

It seems clear that hardware entrepreneurs have (re)learned that iteration speed and hardware-rich development are a more effective way to create new things. Vertical integration is now the dominant solution in mind share. The downside is that it requires tens of millions of dollars and numerous highly skilled employees to kick off. It works for Elon, but not everyone has that skill set.

Amazon Web Services enabled software startups to begin without having to set up on-premises servers, lowering the activation energy. Instant quote, short lead time manufacturing companies and services can do the same for many hardware startups and tinkerers.

The emphasis on speed is because the model only works if the latency is low. The gravity model for frontier technology is much stronger than for existing products. Leading engineers become more productive, iteration cycles shorten, and new ideas become reality faster. Not only does fast service and lightning logistics help convert existing customers, but it also helps create the downstream manufacturers of tomorrow.

Competition, Structural Change, and Strategy